19th century travel in Egypt

Advertisement for Nile cruises by Thomas Cook & Son for the 1898-1899 season*

I recently read Cook’s Tourist’s Handbook: Egypt, the Nile and Desert. (1) This tour company’s guide was written a few years after the well-known travelogue published by Amelia Edwards (in 1890). You can see my review of A Thousand Miles Up the Nile here. As an archaeologist and avid traveller I enjoy reading old descriptions of places, it gives me a sense of how things have changed, and how they have stayed the same.

Thos. Cook & Son (Thomas and John) were renowned travel agents that opened up Egypt (and other parts of the world) to the masses. The company was established in 1871 (2) and ran until 2019 when it went bankrupt. This book is filled with interesting tidbits about the British colonial perspective, the cost of travel and important sites one could expect to see on a 20-day steamboat cruise between Cairo and the First Cataract (Assouan) of the Nile, with an 8-day extension for those passengers who wished to visit Aboo-Simbel and the Second Cataract. A further ‘Forty to fifty days are required for the journey from Cairo to Sinai, Petra, and by Mount Hor, to Hebron and Jerusalem.” (Cook, 1897: 28) A very luxurious two and a half month tour to be sure.

“The benefit of travelling with Cook was that negotiated discounts were passed on to the customers, who would pay the travel sum in a single payment. Cook promised security and ease, opening up travel to a wider public and to women who could now join a package tour unchaperoned.” (van de Beek, 2019) (3)

The handbook discusses issues like arranging for a Turkish visa (Egypt fell under Ottoman rule from 1517-1914), which the tour company could procure on the tourist’s behalf for 8 shillings 6 pence. It includes a reminder that ‘the exportation of antiquities is forbidden without a special permit from the Antiquity department”, (Cook, 1897: 3) and also a discussion on climate, the suggested packing of appropriate day-use and formal wear, and a health section. Thos. Cook suggests that in the event of dyspepsia, diarrhoea, and dysentery, ‘the most simple remedy…is to drink a glass of Nile water fasting.” (Cook: 1897: 5) 💧This latter piece of advice would not likely be given today. In fact, Intrepid Travel advises that in Egypt, “drinking water from the tap is not recommended. Water treatment plants in and around Cairo heavily chlorinate the supply, so the water in the capital is relatively safe to drink. However, it is advisable everywhere else in Egypt to purchase bottled water or drink treated or purified water.” (4)

Cook’s deplorable advice about ‘Backsheesh’ (Cook, 1897: 8) is worthy of replicating in part here, and demonstrates a very colonial attitude, that continues throughout the book.

“Everywhere, from morning till night, the traveller will be tormented with applications for backsheesh…It is the first word an infant is taught to lisp; it will probably be the first Arabic word the traveller will hear on arriving in Egypt, and the last as he leaves it. The word simply means ‘a gift’ but is applied generally to gratuity or fee, and is expected no less by the naked children who swarm around the traveller when he arrives in a village, than be the officials of many public institutions.”

As a salesman he indicates one of the advantages of pre-purchasing hotel coupons includes the threatening thought of being without as “a great drawback to pleasure to arrive in a Foreign town beset by porters, and commissionaires, and rabble, a perfect stranger, and without any definite idea where to go.” (Ibid, p. 9) That would surely encourage (i.e. frighten) tourists to buy from him!

Itinerary from Cairo to Luxor

The planned venture includes 7 days from Cairo to Luxor, including stops in Memphis, Sakkarah (5), Maydoom, Benisooef, Maghaga, Minieh, and Beni-Hassan. “On the way to the tombs the ruins of Beni-Hassan are passed, the villages having been destroyed by order of Mohammed Ali, owing to the incorrigible rascality and thieving propensities of the inhabitants.” (Ibid, p. 17) He certainly does not give an impression of actually liking Egyptians.

By day 5 they arrive and spend a morning in Assiout, which previously was the ‘principal slave market’ (Ibid, p 18). They proceed on to arrive in Keneh by day 7 and visit the Temple of Denderah, after which they will push on to arrive in Luxor before sunset.

Luxor to Assouan

The next several days describe the journey from Luxor to Assouan. Day 8 is spent at the Valley of the Kings and a visit to the “Temple of Hatasoo, called by the Arabs Dayr-el-Bahari”. (Ibid, p. 19)

Frontal view of Deir el Bahari - Hatshepsut’s Temple (2015)

Day 9 sees a visit to both Karnak and Luxor Temples.

Photo: Colossus of Ramesses II at Karnak Temple (2018)

Day 10 continues in Luxor with a visit to the Rameseum, Tomb of Rekhmara, Dayr-el-Medeeneh and Medinet-Haboo, and to view the sitting Colossi.

Photos: L-R Ramesseum (2016), Medinet Habu (2017), Colossi of Memnon (2023)

On day 11, the travellers embark again, with stops at Esneh and Edfou. The following note describes the Temple at Edfou, “which is one of the most complete and best preserved monuments in Egypt…It is in the custody of a Government officer, and beggars are not allowed to pester visitors for backsheesh; but they are more ravenous when one emerges again from the stronghold.” (Cook, 1897: 20)

Day 12 passes by Gebel-el-Silsileh (site of a sandstone quarry), a (limited) half-hour stop at Komombo and on to Assouan.

Photo: Carved scene depicting the crocodile-headed god Sobek at Kom Ombo (2015)

Day 13 and the travellers get to visit Assouan on their own time, followed the next day by a trip to Philae and a chance to see the rapids, where “Nubian men and boys are seen dexterously shooting the Cataract on logs of wood.” (Ibid, p 21) This last phrase was the most exciting description thus far in the book.

Photos L-R: Sunset on the Nile (between Luxor and Edfou); Nile boats at Aswan; Temple columns at Philae (2015)

The return departure starts on day 15 with various stops along the Nile with opportunities to explore or revisit sites, including a stop at Abydus (day 17), which will afford a visit to the Temple of Sethi, Temple of Ramesses II, Kom-es-Sultan and the Coptic Monastery, which are located there; arriving back in Cairo on Day 20.

I took a ‘Princess Sarah’ Nile cruise in 2015 from Luxor to Aswan, with an overland trip to Abu Simbel, and we visited all the same sites. What isn’t captured in this handbook is how friendly the Egyptians are, the beauty of the landscape and riverscape and the amazing architectural delights along the way.

Perhaps in my modern mind-set I wasn’t overly thrilled with this travel handbook, as the attitude was so biased, and often quite negative. Historically, it does provide a rather accurate description of an English businessman’s perspective for the period.

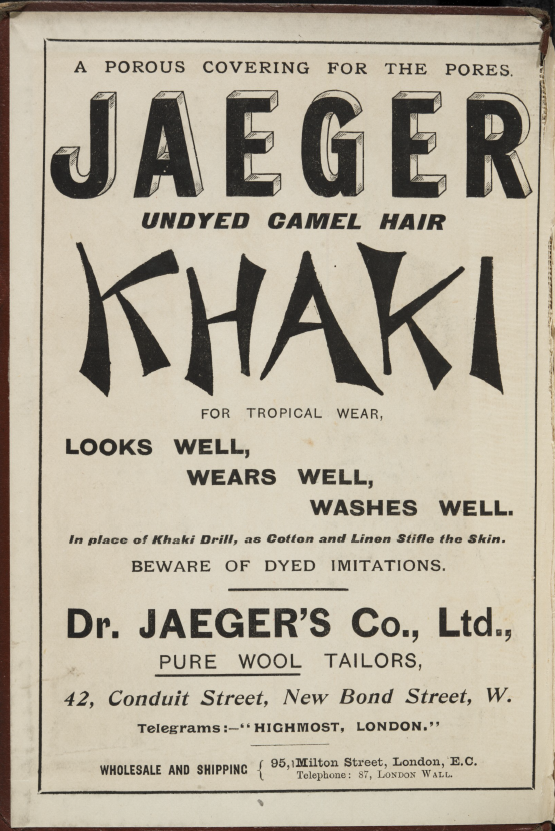

Following the itinerary section the book goes on to provide very dry descriptions of geology, climate, and a listing of wildlife and economic activities, and he quotes the population at that time as being 6,800,000. (Ibid, p 37) Cook then describes the dress and comportment of the men and women of Egypt, and provides an entire sections on ‘Mohammedanism’ and an historical timeline. Prominent sites throughout the country are discussed as well, including Alexandria, Cairo and Gizeh, etc. and a listing of items at some museums. Several maps are also published in the handbook. These sections may be useful for scholars doing research on Egypt for that period. The latter part continues descriptions into Sinai, Jordan and the Levant. Recent Egyptian excavations are listed from p. 346-359. There is a Table of Contents, and an Index is provided starting at p. 375. This is all followed by an appendix of hotels, and a section for advertisements (some of which are quite fascinating, and worth a view).

Sample advertisement 🐪 from Cook’s (1897) handbook

I recommend this handbook to all who wish to venture to Egypt - not as an accurate guide, but more as a vision on the historical context from the time it was written.

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

For some wonderful photos by tourists who visited Egypt in the 19th century, I recommend the collection by Norbert Schiller on the Photorientalist website.(6)

*Heritage sites management: understanding the interrelation among heritage, tourism, and local community urban demands in Luxor City in Egypt - Scientific Figure on ResearchGate. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Advertisement-for-Nile-cruises-of-Thomas-Cook-Son-for-the-season-1898-9-Source_fig6_344631400 [accessed 27 Jul 2024]

(1) Cook’s 1897 handbook is available on JSTOR https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.28047208?workspaceFolderId=0bf4ee10-331d-458f-9d20-844f4f393971&orderBy=updatedOn&orderType=desc&index=0

(2) In 1894 the Egyptian business of Thos. Cook & Son was transferred to a Company registered as Thos. Cook & Son (Egypt), Limited. (Cook, 1897: 13)

(3) van de Beek, N. (2019) Thomas Cook and the way to see the Nile. Blog Post October 27, 2019. https://nickyvandebeek.com/2019/10/thomas-cook-and-the-way-to-see-the-nile/

(4) Intrepid Travel - https://www.intrepidtravel.com/en/egypt/is-water-safe-to-drink-in-egypt [accessed 27 Jul 2024].

(5) Locations and names throughout this article use the spelling as indicated in Cook’s handbook. Modern names are listed with my photos.

(6) Schiller, N. 19th Century Tourist Snapshots: Egypt and Venice.